Few traditions in China are as instantly recognizable as the red envelope, olso called hóngbāo (红包). Traditionally handed out during Lunar New Year, weddings, and family gatherings, they contain money and symbolize prosperity. While the concept of giving money as a gift is simple, the cultural meaning behind the act is layered and profound. Today, understanding the etiquette of red envelopes is an important part of cultural literacy for those who wish to learn Chinese online or with the guidance of an online Chinese teacher, since the vocabulary surrounding this practice often extends into modern life and conversation.

In the past, red envelopes were strictly physical—bright red paper with golden designs, carrying characters such as 福 (good fortune) or 囍 (double happiness). The choice of color itself is meaningful, as red is associated with luck and warding off evil spirits. Parents give them to children as a blessing for health and safety, while newlyweds distribute them to younger relatives as part of wedding customs. Even workplace hierarchies can involve red envelopes, where managers distribute them as a gesture of goodwill to employees.

The digital era has transformed this custom in surprising ways. With apps such as WeChat (微信) and Alipay (支付宝), people can now send virtual red envelopes with just a few taps. During Spring Festival, millions of users flood these platforms to exchange small envelopes in group chats, creating a playful, gamified experience where friends race to grab their share. This phenomenon has even reshaped the way younger generations interact, blending centuries-old tradition with cutting-edge technology.

Etiquette, however, remains crucial. The amount of money given is not arbitrary: certain numbers carry auspicious meanings, while others, like those involving the number 4 (四, sì), are avoided due to associations with death (死, sǐ). Additionally, offering or receiving a red envelope with both hands is considered polite, reflecting the respect embedded in the act.

These small envelopes tell a large story about Chinese culture: one that values family bonds, collective joy, and continuity across generations, even as the tools of tradition adapt to the digital age.

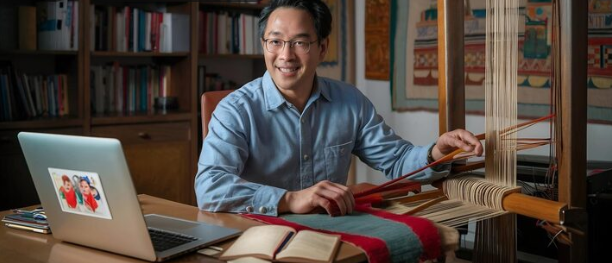

Language learning works in a similar way—traditions live in words, and words live in culture. Language schools like GoEast Mandarin have students explore the connection in a supportive environment through discussions of festivals, modern slang, or also classical expressions. With teachers and also personalized approaches even for children, they can make cultural insights like the story of the hóngbāo part of an engaging language journey.